Suresh Menon – Agency: DNA

I read recently that there are some 60 literary festivals in our country annually. Yet, how many of these dedicate a whole festival or a day of the festival or even a single session to a discussion on that most neglected aspect of literature: translation? We know who wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude, Hopscotch, Name of The Rose, The Unbearable Lightness of Being and a hundred other classics. But how many of us know who translated these works so we could enjoy them in a language we understand?

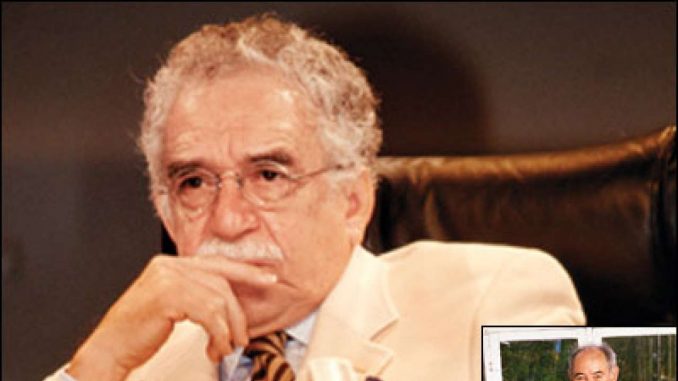

In Kerala, they joke that Marquez is the best writer in Malayalam; that is the language many have read his books in. It is easier to get Malayalam translations of books in Spanish and Portuguese than it is to get one of books in Punjabi or Gujarati. I am sure the reverse is also true. Malayalam novels in Telugu or Bengali? Not so easy. OV Vijayan translated his books into English himself; Girish Karnad writes his plays in Kannada first before writing the English version. These are exceptional men.

Even a modern master like the Guatemalan novelist Eduardo Halfon had five translators working on The Polish Boxer despite the fact that he has lived in America for years and speaks and writes English very well.

It is said of Don Quixote that the original is not as good as Edith Grossman’s translation which the novelist Carlos Fuentes called “a major literary achievement”. That runs contrary to received wisdom: that translation is impossible, that translation is a betrayal, that translation never satisfies, that translation is fraud. There is too the argument that translation ought to be treated as a separate genre independent of fiction, drama, poetry. Grossman has written that “authors must see themselves as transmitters rather than creators of texts.” Borges told his translator not to write what he said but what he meant to say.

Marquez called his translator Gregory Rabassa, “The best Latin American writer in the English language”, and went so far as to say that Rabassa’s version of One Hundred Years of Solitude was superior to his own. He preferred, he said, to read his books in English as translated by Grossman and Rabassa.

These writers, and others like Proust, Dostoevsky, Paz, Pushkin, Chekov, Kundera, Llosa, Allende, Kawabata, Neruda, Pamuk — the list is a long one — would have remained inaccessible but for the work of translators. Translation is long, lonely, even dangerous work, yet translators are seldom seen as creative writers, or given their due as facilitators.

This is only partly because translators tend to write about their work in highly technical terms as if it were a scientific project and every time you put two languages together in a test tube and shook it, you always got the same final translation. Translation is a service, often shining a light on the hidden aspects of a novel.

“Fidelity is our highest aim,” says Grossman, “but a translation is not made with tracing paper. It is an act of critical interpretation. Languages trail immense histories behind them, and no two languages, with all their accretions of tradition and culture, ever dovetail perfectly.”

It is this understanding that gives her book Why Translation Matters a special feel. Rabassa’s If This Be Treason discusses translation and his own role in it with a lightness of touch that reflects the fun he had translating Cortazar, Llosa and others.

Like sculptors who brought out the gods and goddesses hiding in stone at Ellora and Ajanta, Rabassa said that he was merely “exposing the English that was hiding behind Marquez’s Spanish.”

All translations are a compromise between two mutually exclusive exigencies — fidelity to the literality of the words and fidelity to the literary intention of the author. Vladimir Nabokov belonged to the literal school, and his translation of Eugene Onegin strips the original of all poetry. Vikram Seth, whose technique in Golden Gate was inspired by Pushkin pays a tribute to the English translator Sir Charles Johnston with several lines devoted to him. At one point he says, “Pushkin’s masterpiece/ In Johnston’s luminous translation.”

In a collection of essays on the subject, Mouse or Rat?, Umberto Eco speaks of translation as negotiation, arguing that negotiation is not just between words but between cultures. The Italian ‘ratto’ is rat while ‘topo’, he says can be either rat or mouse, and a shriek followed by a cry of ‘Un topo’ is acceptable in an Italian translation of Shakespeare. But in a translation of Albert Camus’s La Peste, the rat presages the plague, and therefore only ‘ratto’ will do.

Susan Sontag has mentioned somewhere three versions of the modern idea of translation — translation as explanation (the translator’s mission is enlightenment, clarification), translation as adaptation (writing another version), and translation as improvement (Baudelaire’s translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s poetry is considered an improvement on the original).

Translation is an art, and like all art can be imprecise. Some writers take it upon themselves to help a translator while others like Marquez see it as a different discipline altogether and leave everything to the translator.

Can there be an untranslatable work? I imagine Finnegans Wake might qualify. Poetry is what is lost in translation, said Robert Frost. Perhaps at the hands of a great translator, the reverse is also true: poetry is what is gained in translation.

All great texts contain their potential translation between the lines, wrote Walter Benjamin. This is as true of Marquez as of MT Vasudevan Nair and Premchand. As Grossman said, “Where literature exists, translation exists. Joined at the hip, they are absolutely inseparable, and, in the long run, what happens to one happens to the other. Despite all the difficulties the two have faced, sometimes separately, usually together, they need and nurture each other, and their long-term relationship, often problematic but always illuminating, will surely continue for as long as they both shall live.”

Rabassa ends his book by expressing his “ultimate dissatisfaction with any translation I have done, even the most praiseworthy.”

In that dissatisfaction lies a profound satisfaction.

The author is editor, Wisden India Almanack

Dejar una contestacion

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.