By Carlos Lozada

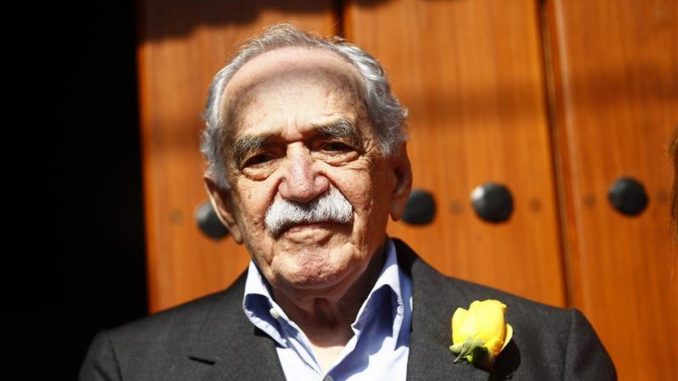

As a translator, it may not get better — or more daunting — than bringing the work of Gabriel García Márquez to new audiences. Beginning with the 1985 novel “Love in the Time of Cholera,” Edith Grossman has rendered in English the Nobel laureate’s work. In an e-mail exchange with Outlook editor Carlos Lozada following the writer’s death on Thursday, Grossman reflects on the art of translation, García Márquez’s pet peeves and which of his novels was her favorite.

When did you learn Spanish?

I first studied Spanish in high school, in Philadelphia. My family were not Spanish speakers.

How did you become a translator?

A friend who edited a magazine asked me to translate a piece by the Argentine Macedonio Fernández. When I said that I was a critic, not a translator, he said, “You can call yourself whatever you want; just translate the piece.” I did, and the rest is history.

How involved was García Márquez in the work of translation?

He was not particularly engaged in the process. On the other hand, I normally don’t consult with an author until I’ve finished the translation. I usually take about six months to do a novel, depending on its length and difficulty.

Did he have any rules about how he wanted his work translated?

He did not like adverbs that ended in -mente (in Spanish; the English equivalent is -ly). I sometimes felt like a contortionist as I searched out alternatives.

Which work of his did you find the hardest to translate?

Everything he wrote was gold. They were all wonderful to work on; I can’t say which was the most difficult.

Do you regret not translating “One Hundred Years of Solitude”?

Yes, of course I wish I’d translated “One Hundred Years.” I wish I’d translated everything he ever wrote.

You’ve said that translation is not about creating an equivalent text from one language to another but that it is a “rewriting of the first text.” What did you mean by that?

Translating means expressing an idea or a concept in a way that’s entirely different from the original, since each language is a separate system. And so, in fact, when I translate a book written in Spanish, I’m actually writing another book in English.

Did you feel you had to get into García Márquez’s head to understand what he meant to convey?

I’ve always felt that you get inside an author’s head by translating his or her work and beginning to see the world through the writer’s eyes. Everything you need to know about an author is in the writing.

As a reader, do you have a favorite García Márquez novel?

I think my favorite may be “Love in the Time of Cholera.”

You also translated his memoir, “Living to Tell the Tale.” How different is it to translate fiction and memoir?

I didn’t approach the memoir differently from the fiction. He used to say that writing journalism and writing fiction are on the same continuum, and he didn’t differentiate them in any hard-and-fast way.

What do you make of the “magical realism” label? Is that the right way to think of García Márquez’s work?

I don’t think the term “magic realism” is especially helpful. All fiction is make-believe that comes out of the imagination and fantasy of the writer. Fictional worlds may use elements of reality, but they are the products of an individual mind.

You’ve also translated Cervantes’s “Don Quixote.”

When [García Márquez] heard that I was going to translate “Don Quixote,” he said, “Dicen que me estás poniendo cuernos con Cervantes” — “I hear you’re two-timing me with Cervantes.” Brilliant!

Who are the young novelists writing in Spanish today that you most admire?

I’m very fond of the work of Santiago Roncagliolo, a Peruvian who currently lives in Barcelona.

What do English speakers miss by reading García Márquez’s work in English? What is lost in translation?

I try not to think about what is lost but what is gained. For the reader who doesn’t know Spanish, this is a chance to read books that otherwise would be out of reach; for English, translation adds to the expressive capability of the language by introducing elements that might not have been there otherwise.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.